King Edward's Music

Tag: Music at King Edward’s School

March 16, 2020

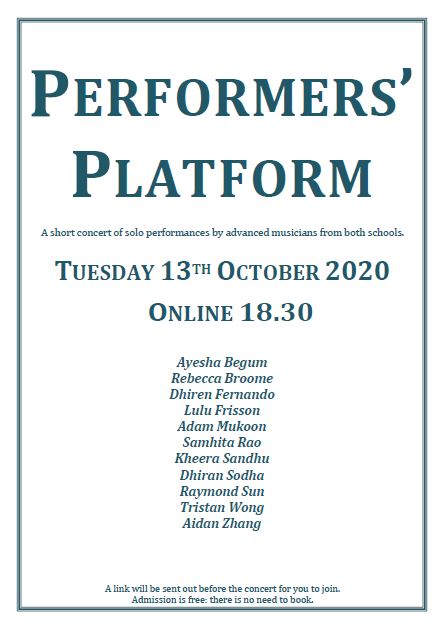

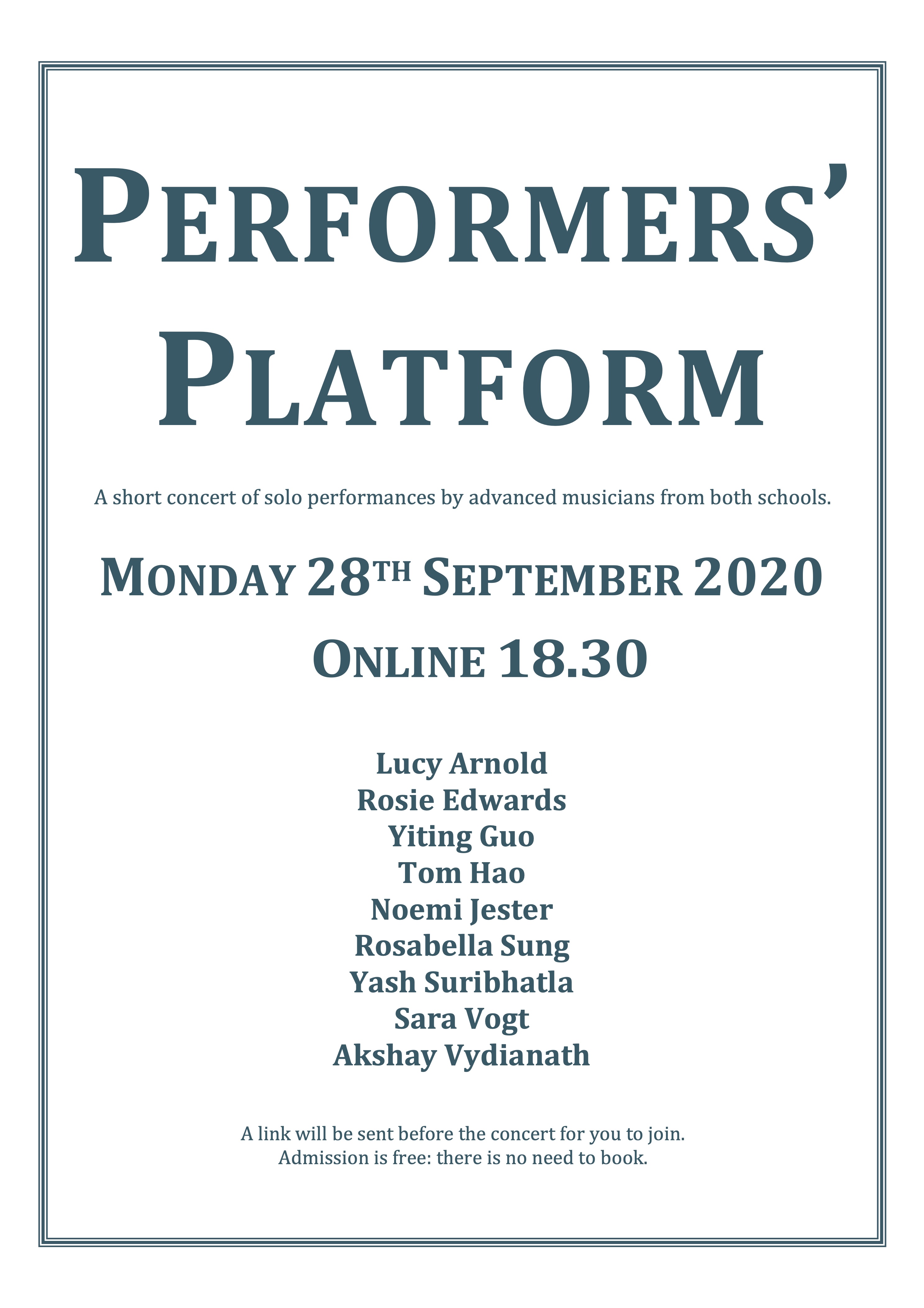

Sexagesimal Concert — the programme

As part of our Sexagesimal celebrations, we produced a short history of KES/KEHS Symphony Orchestra, with contributions from its first players, Chief Masters and Principals, Directors of Music including Peter Bridle, as well as essays by current pupils.

You can read it by clicking the link below:

King Edward’s School, Birmingham, Sexagesimal Programme, KES/KEHS Symphony Orchestra, 2020

Our thanks to Mr. Ash for the photograph.

March 6, 2020

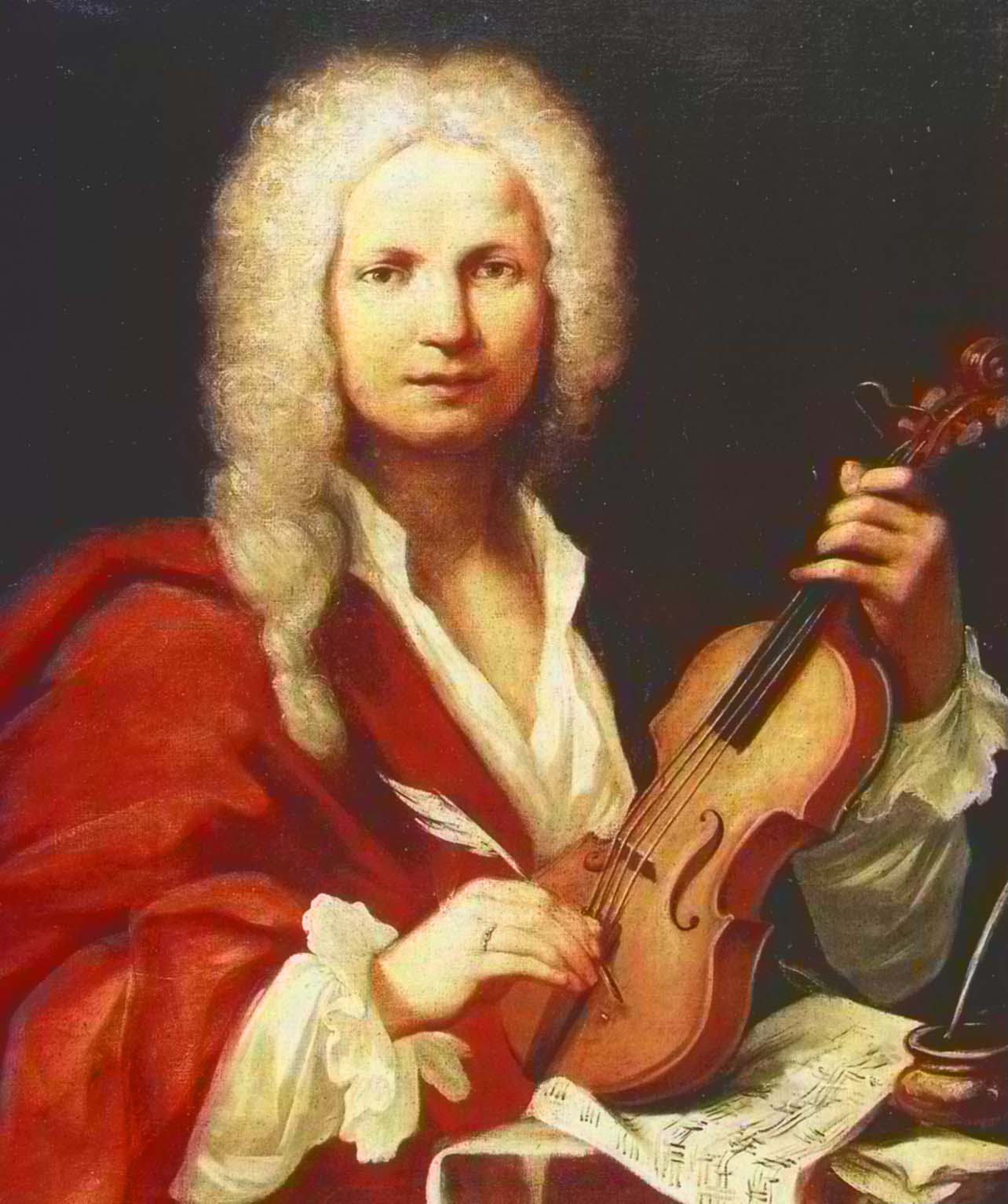

Naina Reddy on Vivaldi’s Gloria

Antonia Lucio Vivaldi, born in 1678, is regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Baroque period. Vivaldi spent his most productive years at the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice as a priest, teaching a variety of instruments and composing instrumental concertos and choral pieces for the girls’ gifted orchestra and choir. Vivaldi was also regarded as a virtuosic violinist and was highly renowned throughout Europe for all his wonderful compositions. Because of this, he enjoyed great success and fortune in his lifetime which he unfortunately wasted on extravagance leading to his death in poverty in 1741. Lots of Vivaldi’s music, including the Gloria, was lost for two centuries until the 1920s when it was rediscovered amongst a pile of forgotten manuscripts.

The Gloria, Vivaldi’s most famous choral piece, was composed around 1715 for the choir at the Ospedale. It presents the traditional Gloria from the Latin Mass in twelve varied movements.

i. Gloria

The opening movement is a joyful chorus with trumpet and oboe obbligato and establishes the triumphant key of D major. The energetic orchestral introduction uses two motifs, one of octave leaps and the other a quaver-semiquaver figure. The choir enters dramatically with a dotted rhythm, announcing the text syllabically. These declamatory outbursts are punctuated by trumpets and oboe which bring a sense of grandeur to the movement

ii. Et in terra pax hominibus

This second movement (“And on Earth peace to all people”) completely contrasts the first as it is in triple time, a minor key and much slower. There are two subjects which appear throughout the movement, woven together in all the voices: “Et in terra pax…” and “Bonae voluntatis…”. The expressive chromatic harmonies in the music create a feeling of tension, which brings to mind how difficult it is for the world to be at peace.

iii. Laudamus te

The third movement is a joyful duet for two sopranos. The texture alternates between sections of simple imitation between the vocal lines and passages in parallel thirds where the voices sing together in cheerful harmony.

iv. Gratias agimus tibi

This six bar long, entirely homophonic movement in E minor uses homorhythm to solemnly evoke praise to God. The declaration of “Gratias agimus tibi” in two short phrases with dramatic pauses in between makes this a grand introduction to the following movement.

v.Propter magnam gloria

This movement, in the same key as the ‘Gratias’, showcases Vivaldi’s skill at contrapuntal writing. The movement is a fugue with the main subject starting in the soprano. It is characterised by four short crotchets followed by a minim and several quavers sung melismatically on the word “Gloria”. The subject is passed through the vocal parts but never sung by all four parts at once, giving the music a playful feel.

vi. Domine Deus

The Largo ‘Domine Deus’ is a beautiful duet between soprano and oboe. The movement is reminiscent of the Siciliana musical style with its dotted rhythms and compound time, which help to evoke a pastoral mood and the oboe adds to this graceful atmosphere.

vii. Domine Fili Unigenite

The ‘Domine Fili Unigenite’ is lively in tempo with the orchestra playing molto energico e ritmico (very energetically and rhythmically). The music embodies the French style of dotted rhythms making it sound like a rousing country dance. Whilst it may sound effortless and cheery, the music is rhythmically tricky as the choir have to be careful not to double dot every note.

viii. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

This Adagio in D minor starts with a brief cello solo introduction followed by a beautiful alto solo. Later on in the piece, every phrase sung by the alto soloist is paired with an antiphonal response from the choir, “Qui tollis peccata mundi”.

These interjections are generally loud with the final response from the choir sounding like a plea with its fortissimo dynamic.

ix. Qui tollis peccata mundi

This movement builds on the words introduced by the choir in the previous movement. Its rich harmonies and expressive chromaticism makes the opening of this movement especially emotive. The slightly faster “suscipe deprecationem nostram” is in triple time and the use of dotted rhythms gives this section a feeling of urgency.

x. Qui sedes ad dexteram

Although an Allegro, the ‘Qui sedes ad dexteram’ continues the serious mood of the previous two movements with its B minor tonality. This movement is originally an alto solo but in this afternoon’s interpretation it will be a bass solo.

xi. Quoniam tu solus sanctus

The ‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ marks the return of the optimistic D major music from the opening movement but introduces some new text: “Quoniam tu solus sanctus, tu solus Dominus. Tu solus altissimus, Jesu Christe.”

xii. Cum sancto spirito

This Allegro double fugue ends the whole work with unstoppable energy and is actually borrowed from a setting of the same text by Venetian composer Giovanni Maria Ruggieri. The two subjects share the same “Cum sancto spiritu…” text but the first subject is introduced by the basses with a marcato bass accompaniment to sound majestic whilst the second subject starts on the off beat and is sung first by the sopranos, sounding much lighter. There are also “Amens” sprinkled throughout the movement to decorate both these subjects but the fff “Amen” at the end of the movement triumphantly ends the whole work.

The dramatic contrasts in mood, distinctive melodies and the rhythmic drive of the music makes Vivaldi’s Gloria one of the most well-known pieces in the repertoire of Choral music.

March 4, 2020

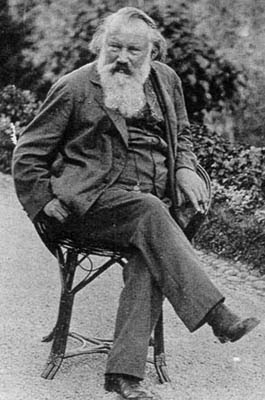

Jacob Rowley on Brahms’s Third Symphony

Johannes Brahms (1833-97): Symphony no.3 op.90

On 31 September 1853, a 20-year-old Johannes Brahms, then completely unknown to the musical world, paid a visit to Robert Schumann to play him his C-major piano sonata. Shortly after this brief preview, Schumann wrote in his diary, “Visit from Brahms, a genius”. It was clear from very early on that Brahms’s music was something special, and in decades that followed the “genius” German, born in Hamburg in 1833, became recognised as one of the finest composers of the 19th century, later to be heralded as one of the three “B”s of classical music alongside Bach and Beethoven. An extreme perfectionist who believed in “absolute music” and rejected music with any programme or narrative, Brahms scrapped anything he didn’t believe to be good enough, regardless of how far through the composition process he was (it took several performances of his First Symphony before he decided to completely rewrite the slow movement), and this is perhaps what accounts for his relatively small amount of compositional output; only four symphonies, four concertos, two serenades, two overtures and a theme-and-variations make up his orchestral works.

Of his four symphonies, the third is the shortest, lasting between 30 and 45 minutes, depending on whether the frequently-omitted repeats are played. However, its length does not detract from how remarkable an achievement this symphony is. It opens with a striking statement of Brahms’s oft-used F-Ab-F motto, followed by a passionato introduction of a theme that bears an unmistakable resemblance to one from Schumann’s Third Symphony; given the close relationship between the two composers, this is unlikely to be coincidental. Though the movement is in F major, and indeed begins with a triumphant F major chord from the wind, the theme more-often-than-not flattens the A, undermining the otherwise straightforward major mode, giving the overall tone of the piece a sense of complex maturity, a feeling aided by the use of a diminished chord as early as the second bar. This unexpected darkening of the music’s character is something that occurs in several places elsewhere in the piece, most notably in the bars immediately preceding the A major second subject, where a sinister F natural in the viola part (darkened further by its repetition by the ‘cellos two bars later) crafts a foreboding set-up for the much more carefree music that follows. The dance-like

⃪ Bob Whalley (KES/KEHS Symphony Orchestra, 1960)second subject offers a moment of calm after the stormy opening, though this respite is quickly dashed by the quick, staccato crotchets that are bounced around the string section before the intense lead-up to the development. The relatively short development, where the second subject returns in a sinister C# minor, is concluded by a triumphant restatement of the F-Ab-F motto, leading directly into the recapitulation. The coda brings the movement to an atypically quiet end, though quiet endings become something of a theme throughout the symphony.

The storm clouds subside for the first (for there are two in this symphony) slow movement. It offers a striking textural departure from the previous movement, being mainly wind-dominated and featuring huge amounts of empty space in the string parts for the wind and brass to quietly tiptoe above. The dialogue between the strings and woodwind is inspired by folksong, and its simplicity and pastoral quality create a colourful landscape of blissful tranquillity. The mood suddenly brightens with a semiquaver-based decoration of the melody by the oboe and strings, though this is soon replaced by a mysterious atmosphere of uncertainty, with a simple motif of two repeated notes that echoes throughout the orchestra through “a kaleidoscopic spectrum of harmonies”. After the recapitulation brings us back full circle, the movement fades away, leaving nothing but complete stillness and calm.

The famous third movement is driven by its breathtakingly expressive ‘cello melody. This haunting theme is encircled by a delicate glimmer of strings, an accompaniment that gradually intensifies as the piece progresses. Although it moves through several different keys and textures, the movement never loses its evocative intimacy, as every repetition of the theme adds a new layer of emotional intensity that only serves to fuel the shadowy aura surrounding it. Any slight humour implied by the syncopation of the bass line in the middle section is spoiled by the menacing teasing of the main theme by the woodwind that leads to the full return of the opening section. It is here that the opening theme feels the most isolated, as it is played by a solo horn, so that it sits outside the texture while the strings rustle in a whispered business around it.

And so we come to the very end, with a finale that opens with a winding, dactylic theme in octave unison that is meant to remind the listener of the finale of Brahms’s Second Symphony, composed six years earlier. As soon as the music begins to gain some momentum, with the entry of the flutes and clarinets being supported by a steady plod from the double basses, it is brought to a grinding halt by a solemn, serious chant driven by the strings. However, a sforzando upbeat at the end of this section launches the orchestra back into a frantic aggression, and though the second subject, on C major, livens the mood, the music nonetheless retains its energetic rhythmic drive. Invasive recollections of the opening motif add to the polyphonic chaos, which reaches its peak during the development, where, after a short but dramatic silence, a return of the chant from the exposition, now blasted out by the brass, is surrounded by a furious flurry of triplets in the string section. The return of the opening theme in the recapitulation appears far more violent than its initial iteration. Soon, however, the chaos once again subsides, and as the piece gradually fades away, a faint echo can be heard of the very opening theme of the symphony.

Jacob Rowley, Sixths